A blog about Zionism, Jewish identity, and antisemitism.

© 2025 Michael Jacobson. All rights reserved.

In the western imagination ‘indigenous peoples’ are generally Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders, Polynesian peoples such as the Māori, and the pre-Columbian peoples of the Americas — all of whom were dispossessed of their lands by Europeans in the early modern period. Indeed, much of the terminology around indigeneity was coined to describe these peoples. But this doesn’t invalidate its use to better understand and protect other, equally applicable, peoples — including the Jewish people.

According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs:

Indigenous peoples are inheritors and practitioners of unique cultures and ways of relating to people and the environment. They have retained social, cultural, economic and political characteristics that are distinct from those of the dominant societies in which they live. Despite their cultural differences, indigenous peoples from around the world share common problems related to the protection of their rights as distinct peoples.

Indigenous peoples have sought recognition of their identities, way of life and their right to traditional lands, territories and natural resources for years, yet throughout history, their rights have always been violated.

Further to the above, both the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues and Amnesty International offer a number of criteria for identifying indigenous peoples. I will list each of these below, and demonstrate their applicability to the Jewish people.

Jews have always regarded themselves as members of a single Jewish nation (Am Yisrael). And, since the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, have understood that they are in a state of exile (galut) from their ancestral home — the Land of Israel (Eretz Yisrael).

The collective memory of our people’s forced removal from Eretz Yisrael — and the hope of our eventual return — have been integral parts of Jewish belief and identity for nineteen centuries. Our traditions demand that we must never forget Jerusalem, and that it should be in our thoughts even during our happiest hours. Three times each day, traditionally observant Jews face towards Jerusalem to pray. We mourn the destruction of our temples annually on Tisha B’Av and, during Pesach and Yom Kippur, we pray for ‘next year in Jerusalem!’

We are, and have always been, one people — indigenous to Eretz Yisrael. It was there that our identity as a nation was forged, that our language and script developed, that our beliefs, customs, and traditions began. To us, it is the most sacred place in the world — it is where our ancestors and prophets lie buried, and represents not only our past but also our future.

Despite almost three millennia of foreign control over the land — under the Assyrian, Babylonian, Achaemenid, Macedonian, Seleucid, Roman, Byzantine, Arab, Ottoman, and British empires, respectively — there has been a distinct and continuous Jewish presence in Eretz Yisrael.

Recent studies into Jewish population genetics show that members of the three main Jewish diaspora groups — Ashkenazim, Sephardim, and Mizrahim — have a common Levantine origin, and generally share more genetic commonality with one another than with the majority populations among whom they have lived. These findings are hardly surprising given the rarity of post-exilic Jewish proselytising, and the fact that traditional Jewish law forbids marrying out of the nation. Voluntary intermarriage with non-Jews was almost unheard of until the late 19th century.

These modern gene studies, alongside extensive historical and archaeological evidence, substantiate the traditional Jewish belief in our shared Middle Eastern origins and peoplehood. It is very important to note, however, that Jewish identity is not determined by genes or ‘blood quantum’, but by recognition as a member of the nation, by the nation. Jews are normally born to a Jewish mother, or undergo a formal process of adoption by the nation known as giyur (usually translated as ‘conversion’).

Traditional Jewish life has — at all times and in all places — been oriented around the Land of Israel. Despite generations of exile, Jews have always felt a profound spiritual connection to our ancestral land, and the Jewish calendar follows its seasonal rhythms — the year is punctuated by festivities that correspond to agricultural milestones in Eretz Yisrael.

The civil year begins on Rosh Hashanah, the first day of the month of Tishrei, which coincides with the beginning of the rainy season. During Rosh Hashanah, it is considered a great mitzvah (divine commandment, holy or righteous act) to hear the sound of the shofar — a simple trumpet crafted from the hollowed out horn of a kosher animal, traditionally a ram. It is also customary to celebrate the occasion by eating and sharing honeyed foods and sweet fruits, such as dates and pomegranates, which symbolise our hope for a joyful and bountiful year ahead.

Sukkot, also known as the ‘Harvest Festival’ (Chag HaAsif), celebrates the autumn harvest. During the festival Jews construct and decorate booths (sukkot), in which we eat meals, entertain guests, and give thanks for the harvest. These sukkot represent both the makeshift shelters the ancient Israelites dwelt in during their forty year sojourn in the desert, and also the simple huts that Jewish farmers would live in during the last hectic period of harvest before the coming of the winter rains.

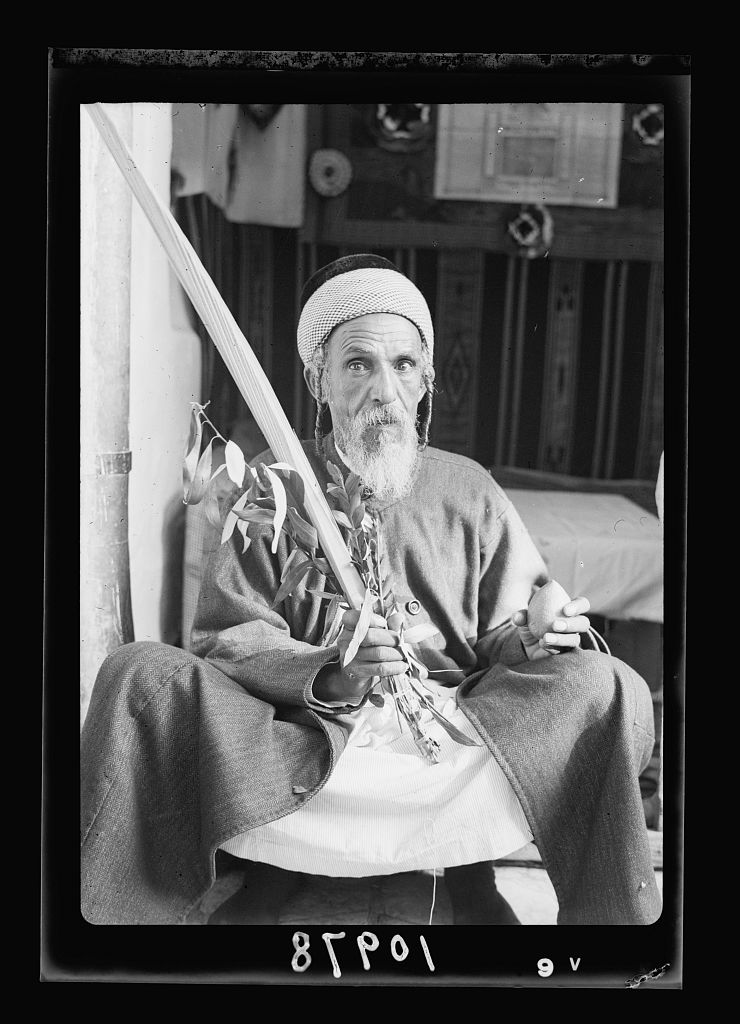

Another important part of the Sukkot celebration is the ritual waving of the lulav and etrog. Although the word lulav specifically refers to a palm frond, the term is widely used as shorthand for bundled branches of palm, myrtle, and willow. The etrog is a citron, which tradition dictates should be healthy, yellow, and beautiful.

The seven-week period that marks the beginning of the grain harvest in Eretz Yisrael is bookended by the festivals of Pesach and Shavuot. These festivals also commemorate the Israelite exodus from bondage in Egypt, and our receiving the gift of Torah at Mount Sinai, respectively.

Responsible stewardship of our ancestral land is of great importance to Jews. This value is perhaps most clearly exemplified by the mitzvah of the sabbatical year (shmita) — Jewish law states that the Land of Israel should be left fallow every seventh year, which reminds us to maintain a harmonious and sustainable relationship with the natural world. Furthermore, the prohibition against wanton destruction (bal tashchit) teaches that we are forbidden to be wasteful of natural resources, and must not kill animals needlessly.

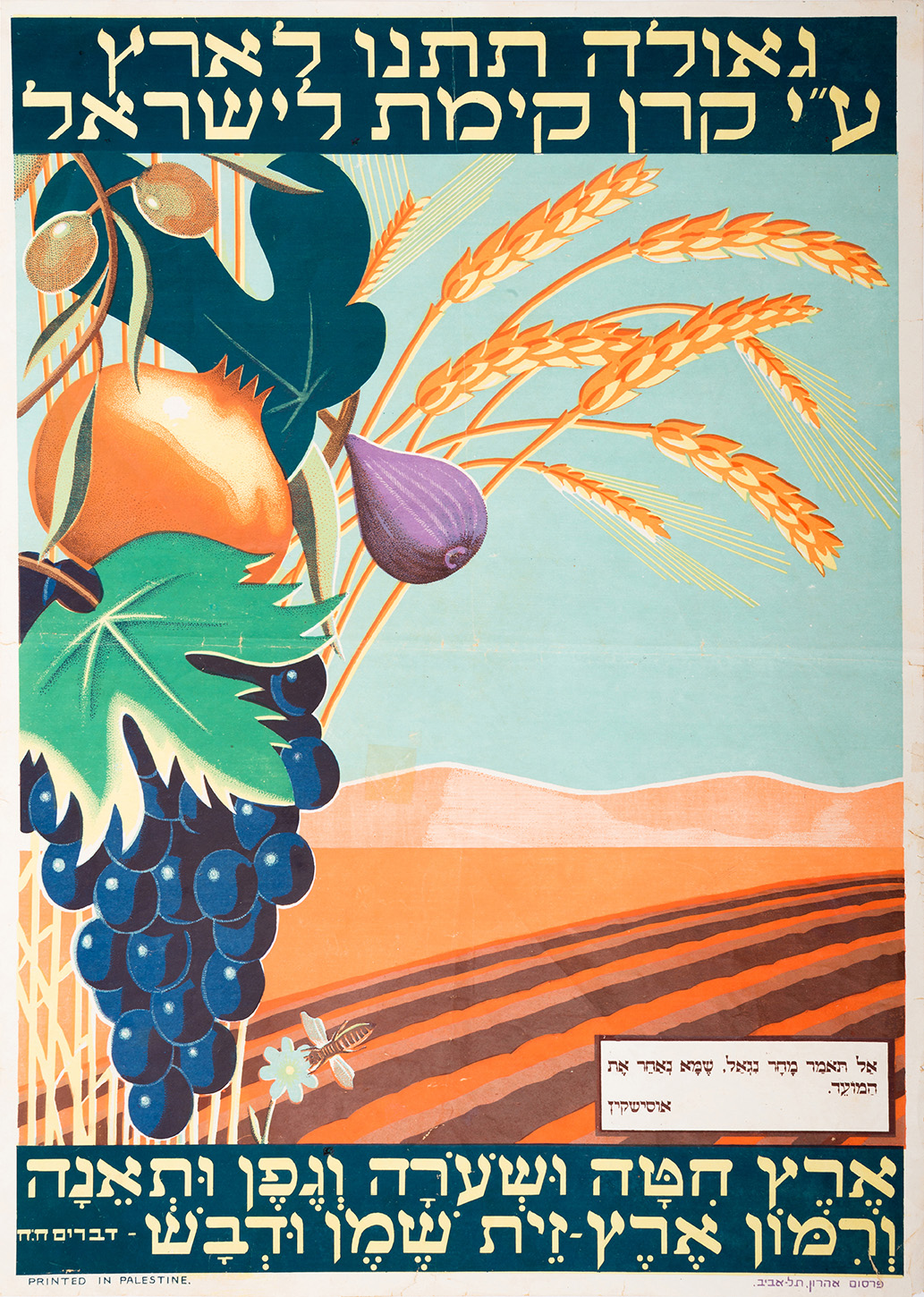

Jewish ethnobotanical traditions are also based on plants native to Eretz Yisrael, and the ‘seven species of the Land of Israel’ — wheat, barley, grapes, figs, pomegranates, olives, and dates — have long been understood to possess important symbolic, medicinal, and spiritual properties.

Many traditional Jewish names describe Levantine flora and fauna — examples include Devorah (bee), Dov (bear), Arieh (lion), Tzvi (deer, gazelle), Ze’ev (wolf), Yonah (dove), Alon/Ilana (oak tree), Oren (pine tree, bay tree), Tamar (date fruit, date palm, palm tree), Shoshana (lily), and Hadassah (myrtle).

The coastal waters of the Mediterranean Sea (known to our ancestors as HaYam HaGadol — the Great Sea) are home to the chilazon — a sea snail from which tekhelet, a vibrant indigo-blue dye, is obtained. The Torah instructs Jews to affix ritually knotted fringes (tzitzit) to our garments, one of the threads of which should be dyed with tekhelet. Our sages teach that when we gaze upon tzitzit we are guided through a series of spiritual associations — first we are reminded of the blue of the ocean, then of the clear midday sky, and finally of God’s sapphire throne. As a result of ancient Roman edicts, and the later Islamic conquest of the Levant, the process of creating tekhelet was lost for centuries, and all tzitziyot were plain white. Production of this special dye was only revived following the re-establishment of Jewish sovereignty in the modern State of Israel.

There are three main divisions within the Jewish nation, membership of which is inherited from one’s father. Leviim belong to the Tribe of Levi, Kohanim are members of the priestly line — descended from Aaron the High Priest (Kohen Gadol), who was himself a Levite — while all other Jews are known as Israelites (Yisraelim).

Prior to the razing of Jerusalem in 70 CE by the armies of Roman Emperor Vespasian, Kohanim had special privileges and responsibilities in the Temple; these included offering sacrifices, burning incense, cleaning and lighting the menorah, and administering the Priestly Blessing (Birkat Kohahim) twice daily.

In modern times Kohanim recite this blessing each morning when in Jerusalem; elsewhere in the Land of Israel customs vary, and in the diaspora it is usually only delivered during major holiday services. During the recitation of the blessing it is customary for all worshippers, including the Kohanim, to cover their heads with prayer shawls (tallitot). During synagogue services, in traditionally observant Jewish communities, Kohanim are called first to the Torah, followed by Leviim, and then Yisraelim. Jewish law (halacha) states that Kohanim are forbidden to marry divorcees or converts (gerim), and are subject to strict rules regarding their proximity to dead bodies or graves.

Halachic affairs are traditionally adjudicated by a rabbinic court (beit din), usually comprising three halachic judges (dayanim). Modern dayanim are typically rabbis, and are often also lawyers, trained in relevant state laws. Halacha states that Jews are bound by the civil law of any country in which they live (dina d’malkhuta dina), and that this should take precedence over Jewish law in certain matters, if the two systems are at odds. Batei din are convened to rule on numerous community matters such as inheritance or business disputes, marriage eligibility, kosher certifications, divorces, and ‘conversions’.

Another traditional part of Jewish life is tzedakah. Today the word is usually translated as ‘charity’, but more accurately refers to ‘righteousness’ or ‘justice’. Giving money, or other material resources, to impoverished members of the community is not seen as an act of beneficence — above and beyond what is required — but rather a moral imperative. The poorest in a community are also expected to make a contribution to others, even if it is largely symbolic. Jewish philosophical and legal writing regarding tzedakah demonstrates that, historically, this practice was more reminiscent of the modern welfare state than of charitable donation.

‘Judaism’ — a 17th century English translation of Judaismus, itself a Latinised form of the Ancient Greek Ioudaismos (Ἰουδαϊσμός), meaning roughly ‘the way of the Jews’ — is best understood as the collected laws, customs, and beliefs of the Jewish people; this includes not only halacha, but also aggadah (folklore, legends, fables). A deep dive into this ‘collection’ is far beyond the scope of this essay, but I will highlight a few traditional aspects of Jewish life.

Hebrew is the ancestral language of the Jews, and was widely spoken until at least the 2nd century CE.1 Since that time it has always been studied and used by Jews but — until the 20th century — mainly as a liturgical, legal and literary language, and as a lingua franca for communication between distant Jewish communities.

Over the many centuries of exile from our homeland, numerous diasporic Jewish languages have evolved, the most widely-spoken of these in the modern era are Yiddish (Judeo-German), Ladino (Judeo-Spanish), and Judeo-Arabic. These languages are usually written in Hebrew scripts, and their lexicons typically include a large number of Hebrew and Aramaic loanwords.

Jewish cookery, both in Israel and the diaspora, has three main influences — the Levantine origins of the Jewish nation, traditional Jewish dietary (and other) laws, and the cuisines and ingredients native to the regions in which Jews have dwelt during our exile. There is perhaps no better example of this than cholent — a hearty meat stew that has been a permanent fixture of Jewish Shabbat tables since antiquity.

Cholent (also known as hamin) is traditionally prepared on a Friday afternoon and kept overnight in a preheated oven or slow cooker, so that it can be eaten hot on the sabbath without the need to kindle or extinguish a fire. Until recently it was common for the stew to be cooked, and kept hot, in the oven of the local Jewish baker. Variations of this dish have been eaten by Jews for at least two millennia. Ashkenazi cholent today is generally made with beef, potatoes, beans, and barley; Sephardi and Mizrahi cholents are usually similar to those of Ashkenazim, but often include whole eggs, and are sometimes made with chicken instead of beef.

In addition to rituals and customs concerning day-to-day living and rites of passage, there are many ancient Jewish traditions regarding death and mourning. Cremation is considered forbidden, and tradition dictates that a Jew should be buried as soon as possible following their death, usually within two days. Before interment the body must be washed and ritually purified. This important and solemn duty is carried out by volunteers from the community’s burial society (chevra kadisha).

Shiva is the traditional seven-day mourning period observed by families following the death of a loved one. During this period it is customary for all the mirrors in a mourning home to be covered, a candle to be kept lit at all times, and mourners to sit on low stools or cushions.

Each year, on the anniversary of a loved one’s death (according to the Jewish calendar), it is traditional to light a memorial candle that will burn for twenty-four hours. Some Jews also fast on this day, and many visit the grave of whomever they are commemorating. Today this observance is best known by its Yiddish name — yahrzeit (anniversary).

Throughout centuries of exile, Jews have been victims of thefts, massacres, rapes, forced conversions, and mass expulsions. We have been segregated and made scapegoats, pariahs, and symbols of evil and disease incarnate. Our professions, clothing, and places of residence have been mandated by the whims of countless governors, monarchs, emperors, and both Christian and Muslim religious leaders. This persecution has been widespread throughout the world, not least in Europe, but I’m going to focus here on the treatment of Jews in our ancestral land.

Since the State of Israel was founded on 5 Iyar 5708 — 14th May 1948 in the Gregorian calendar — Jews, as Jews, have not been persecuted by the government in our homeland. However, this event marked the end of fourteen centuries of discrimination against, and marginalisation of, Jews under successive Islamic empires.

Although Judea had been captured centuries earlier by the Roman Empire, it was the Muslim-Arab conquest in the 7th century, and subsequent Arab colonisation, that paved the way for the centuries of Islamic hegemony that preceded the establishment of Israel. Under each of the Islamic caliphates — Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid, and Ottoman — Jews were categorised as dhimmis.

Dhimmis were ostensibly ‘protected’ under traditional Islamic law (sharia), but in practice this ‘protection’ was often little more than legally sanctioned discrimination and humiliation. Jews were typically forbidden to carry weapons for self-defence, but were often subject to pogroms, and were rarely protected by the authorities. Under their Islamic conquerors Jews were subject to extortionate and degrading taxation, were relegated to vulnerable ‘Jewish quarters’ or ghettos, and were segregated in communal spaces like markets and bathhouses. They were required to show deference to Muslims at all times — giving up seats to them, and stepping out of their way on public streets. Jews could be executed if they were found guilty of criticising or mocking Islam or Muhammad, or even inadvertently touching a Muslim woman, but were not allowed to give evidence in courts to defend themselves.

It is important to note that the dhimma laws were applied inconsistently throughout the Islamic world, and some Jews enjoyed fragile periods of relative tolerance, even achieving prosperity and political influence at times. However, in Eretz Yisrael, particularly in our four holy cities — Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and Tiberias — Jews generally lived in extreme poverty, often relying on financial aid from diaspora communities. Suffice to say that Jews, in their native land, were indeed ‘marginalised and discriminated against by the state’.

At its core, Zionism is simply a political movement to recognise Jewish peoplehood, establish and maintain a sovereign Jewish nation state in our ancestral land, and safeguard both Jewish lives and Jewish culture from external threats.

Today the shmita law is observed once more. Tekhelet production has resumed. Hebrew has been modernised and revived as the vernacular in the Jewish state, and a modern Hebrew literary tradition has developed, influenced not only by the modern world, and the struggle for national liberation, but also millennia of Jewish history and culture. Batei din form part of the state legal system in Israel. The Jewish calendar is used, alongside the Gregorian, as a civil calendar. All members of the Jewish nation are entitled to citizenship in the Jewish state, and are thus guaranteed refuge from any future violence or persecution in the diaspora. Sacred Jewish rites — such as male circumcision (brit milah), which is outlawed in Iceland, and kosher slaughter (shehita), which is illegal in Belgium — are protected from non-Jewish government interference. Jews are able to live and pray in Jerusalem, our capital city, according to our traditional ways, and to be buried among our ancestors in our historic homeland.

We Jews are a unique and distinct people, but we are certainly not the only people for whom this is true.

Arguably the most ‘iconic’ indigenous peoples are those who lost their lands and sovereignty as a direct result of the establishment, and subsequent western expansion, of the United States of America. Native Americans, as they are commonly known, are by no means a monolith — there are currently 574 federally recognised tribes in the US, whose traditional beliefs and languages vary enormously. Today the Cherokee people comprises three of these federally recognised tribes — the Cherokee Nation, the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

To be a Cherokee, according to historic customs, a person usually had to be born into one of the seven Cherokee clans — Wolf, Deer, Bird, Paint, Blue, Wild Potato, and Long Hair; clan membership was conferred matrilineally. Principal Chief John Ross, whose ancestry was primarily Scottish, was a born Cherokee via his maternal grandmother.

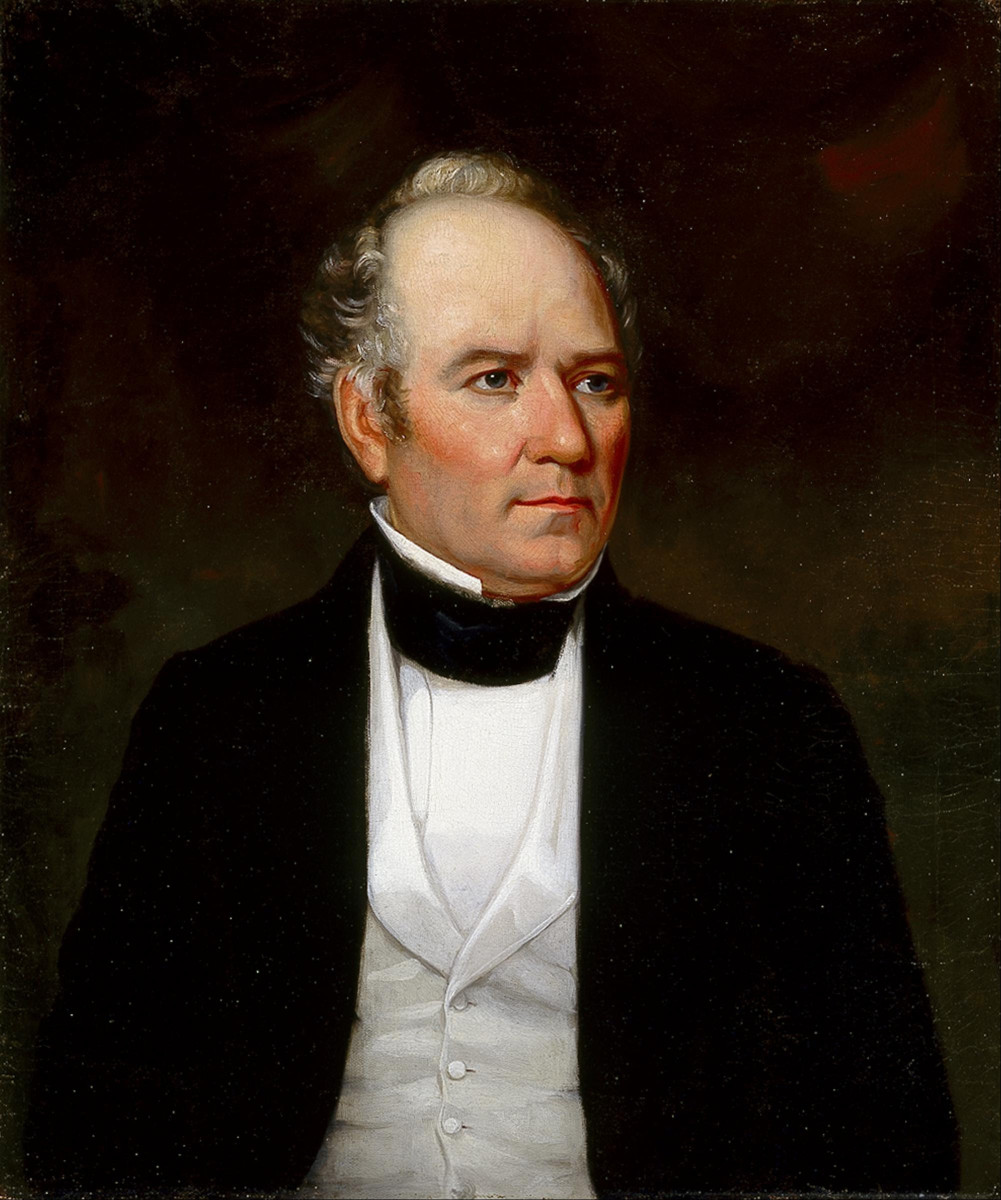

It was also possible to become a Cherokee by being adopted into, and accepted by, the tribe. There are many examples of Europeans becoming Cherokees, perhaps the most famous of which is Sam Houston (1793 - 1863), for whom the city of Houston, Texas is named. Houston was born to Scotch-Irish Presbyterian parents, but was formally granted Cherokee tribal membership in 1829.

Following the Emancipation Proclamation, the Union victory in the American Civil War, and the US-Cherokee Treaty of 1866, many African-American slaves previously owned by Cherokees were given tribal citizenship; these are the so-called ‘Cherokee Freedmen’, whose descendants fought a proposed revocation of their tribal membership in recent years.

Traditional Cherokee laws regarding tribal membership have given way to modern legislation concerning blood quanta (used as a membership criterion by the United Keetoowah Band and the Eastern Band, but a highly controversial subject among Cherokees), or proven descent from individuals listed in the Dawes Rolls — a US census compiled between 1898 and 1906.

Cherokees were traditionally a settled people, whose historic nation comprised a great many towns and villages in parts of what are today the States of Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. Cherokee buildings were usually constructed using the wattle and daub method until the 19th century, when log buildings became more common. In addition to family homes, Cherokee towns typically featured a communal ‘council house’ — a spiritual and municipal building. These council houses were often heptagonal, with the seven sides representing the seven Cherokee clans, and would typically contain a ‘sacred fire’, which was always kept burning, and was used to kindle the individual hearth fires of homes in the town. This fire holds great symbolic significance for Cherokees. Indeed, the official seal of each of the modern Cherokee tribes features a seven-pointed star inside a wreath of oak leaves, which represents ‘the eternal flame of the Cherokee people’.

Although not a strictly monotheistic people, Cherokees traditionally believed the world, and all things, to have been made by Unetlanvhi (Great Spirit, Creator). Traditional Cherokee culture and theology were based on the agrarian and land-based identity of the tribe — the year featured several festivals marking agricultural events. The Green Corn festival, a first fruits ceremony, celebrated and gave thanks for the summer corn harvest, and often featured ritual dancing and waving of ears of corn. And the autumnal Great Moon ceremony was the traditional new year celebration. Many Cherokee festivals involved fasting, feasting, purification ceremonies, and ritual immersion in water.

Women would separate themselves from the rest of the town or village when they were menstruating, usually in a hut built for this purpose. While in this hut they would be brought food and drink by non-menstruating women, but they were strictly forbidden from taking part in ceremonies or preparing food. After menstruation a woman would ritually bathe in fresh running water, and put on clean clothes, before returning to her home. Men were forbidden from having sexual intercourse with menstruating women, and if they did so they too would have to perform a ritual of purification and cleansing.

Cherokees traditionally believed that people would literally take on the characteristics of animals they ate, and so many avoided eating meat from cows and pigs2, as these creatures were seen as sluggish and ungraceful. Birds of prey were generally considered unclean, and so were traditionally not eaten either.

There was a longstanding Cherokee tradition of collective ownership, and communal distribution of both labour and material resources, with members of the community taking foodstuffs and materials according to their needs. Gadugi (Cherokee: ᎦᏚᎩ), is a term that describes ‘working together’, and traditionally referred to groups of Cherokees who would collaborate on tasks such as harvesting crops, or caring for elderly members of the tribe.

A Cherokee would typically be buried one day after their death, following washing and purification of their body by a close family member. A ritual seven-day grieving period was traditionally observed after the loss of a loved one, and was usually overseen by a didanawisgi (usually translated as ‘medicine man’), who would also offer counsel to mourners. In the Cherokee context, ‘medicine’ refers not just to physical but also spiritual health. A didanawisgi would also traditionally be an expert on Cherokee language, history, and theology, including the correct way to conduct lifecycle ceremonies, etc.

The Cherokee language belongs to the Iroquoian language family, and historically did not use a writing system. In the early 19th century, the Cherokee syllabary was developed by Sequoyah (c. 1770–1843), a Cherokee polymath. Using his syllabary, Sequoyah signed his name ᏍᏏᏉᏯ — ‘s-si-quo-ya’. Following the invention of the syllabary, and its formal adoption by the Cherokee Nation in 1825, literacy spread rapidly among Cherokees and many tribal customs, laws and medicinal recipes were codified. This new system of writing was also used by Moravian missionaries to translate the New Testament into Cherokee, to facilitate the spread of Christianity among Cherokees. The Cherokee Phoenix — published in both English and Cherokee — was founded in 1828 in New Echota, then the capital of the Cherokee Nation. The Phoenix was the first Native American newspaper, and the first bilingual newspaper in the United States.

The Iroquoian roots of the Cherokee language suggest the possibility of an origin in the Great Lakes, but Cherokee tradition holds that the tribe’s original town was Keetoowah (Cherokee: ᎩᏚᏩ), in the Great Smoky Mountains. Following the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Cherokee people were expelled from their homelands by the United States government, and were forced to settle in federal ‘Indian Territory’ in Oklahoma. This forced migration came to be known as the ‘Trail of Tears’, and resulted in the deaths of an estimated 4,000 Cherokees — approximately twenty percent of the tribe. Many Cherokee elders died during this gruelling exodus, resulting in a great loss of oral history, and knowledge of traditional Cherokee lifeways.

Throughout this section I have generally referred to traditional Cherokee customs and practices in the past tense. This is not because the Cherokee people no longer exist, or that they have abandoned these traditions — far from it! Although the majority of Cherokees today practice some form of Protestant Christianity, a considerable number continue to follow the ways of traditional Cherokee theology. I have gone to painstaking effort to accurately and respectfully describe these traditional Cherokee ways: consulting historical literature sold by the Cherokee Nation itself, engaging in conversation with contemporary Cherokees, and using historical testimony from Cherokee people wherever possible. However, I am not a Cherokee, and it would not be appropriate for me to make proclamations on what is ‘authentic’ Cherokee culture today. I respect the Cherokee people and their right to self-determination, free from the forced imposition of foreign anthropological or ‘identity’ frameworks.

At this point, I suspect many of my non-Jewish readers will be wondering why they’ve just read several paragraphs about Cherokees in an essay that is, at least nominally, about Jews. Jewish (and perhaps Cherokee) readers, however, will probably be struck by the remarkable parallels between traditional Cherokee and Jewish customs and practices.

When Europeans first encountered Cherokees, many contemporary thinkers were fascinated by the similarities between their ways and the ways of Jews. Some even hypothesised that Cherokees, and certain other tribes, were descended from the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. One such theory was outlined in detail by Puritan minister Thomas Thorowgood in his 1660 work Jews in America, or Probabilities, that those Indians are Judaical, made more probable by some Additionals to the former Conjectures. Another notable proponent was the 18th century Irish historian James Adair, whose 1775 book History of the American Indians contains several chapters devoted to this subject.

Despite conjecture, there has been no credible evidence produced to support this thesis; any historical similarities between the Jewish and Cherokee peoples are almost certainly coincidental. But there are many similarities nonetheless: in our traditions regarding tribal/national membership, in our relationship to the natural world, the ways we count and mark the passage of time, how we bury and mourn our dead, our festivals, our dietary customs, our beliefs and laws regarding ritual purity and immersion in water, and the inclusion of a holy ‘eternal flame’ in our symbolism and theology.

Even the 19th century Cherokee expulsions have certain parallels with historic Jewish expulsions: the United Keetoowah Band trace their origins to a group of Cherokees sometimes known as the ‘Old Settlers’, who began to migrate west of the Cherokee homelands before the Trail of Tears officially began. Then there is Cherokee Nation, the largest of the modern Cherokee tribes, whose ancestors were forced to walk the thousands of miles of the Trail of Tears, and settled in Oklahoma alongside the United Keetoowah Band. And finally there is the Eastern Band, whose forebears managed to largely escape the forced expulsions of the 1830s and continued to live in, and rebuild, the historic Cherokee lands. Sephardim and Ashkenazim are the descendants of Jews who were exiled from our homeland, or who had already migrated to Europe for trade prior to the exile, whereas Mizrahim descend from those Jews who stayed in Eretz Yisrael, or built communities elsewhere in the Middle East and North Africa. These groups are all equally Jewish — despite some cultural and liturgical differences which developed in exile — and have all yearned for a return to our homeland, and for the revival there of Jewish sovereignty and self-governance.

It has often been said that ‘comparisons are odious’ or, as Dogberry — the self-satisfied and malaprop-prone night constable in Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing — has it: ‘comparisons are odorous’. Though if used wisely, comparisons can also be illuminating, and can help to expose double-standards and hypocrisy.

Jews are not ‘adherents of Judaism’, rather ‘Judaism’ is the way of the Jewish people. Our theology and laws are our own, they are not universal, and cannot be divorced from our peoplehood. A non-Jew can fully, and sincerely, believe all Jewish teachings, and follow all Jewish laws, but this does not automatically make them a Jew. Though anyone can choose to become a Jew.

The fact that we do not fit neatly into contemporary European-American identity frameworks, with their narrow and paternalistic emphasis on skin colour, does not make us wrong. If an academic framework seeks to truly understand Jews, but is unable to understand and accept us as we understand ourselves, it is flawed — we are not.

In accordance with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the Cherokee tribes are sovereign and self-governing, they decide who qualifies for tribal/national membership, and therefore who is eligible to actively participate in their democracy. For example: a person must be an enrolled member of the tribe to run for the office of Principal Chief, and one must be a Cherokee (according to criteria set by Cherokees) to be enrolled as a member of the tribe. Israel was founded as the nation state of the Jewish people. It is not an exclusively Jewish country — those Arabs who remained in Israel after the war of 1948, and their descendants, enjoy full Israeli citizenship today. Israeli citizenship is also open to foreign-born non-Jews via naturalisation — but all Jews, regardless of their place of birth, automatically have the right to Israeli citizenship.

Being a Jew is not, and has never been, predicated on the colour of one’s skin, or the place of one’s birth. We are a people and a nation, not a ‘race’ — we are not, and do not seek to be, genetically or ‘racially’ homogeneous. In 1973 Ovadia Yosef, then Sephardi Chief Rabbi of Israel, ruled that the long isolated Beta Israel community were Jews, possibly descended from the Tribe of Dan. In May 1991, as the political and economic stability of Ethiopia was collapsing after decades of civil war, the Israeli government grew concerned about the welfare of remaining Beta Israel Jews in Ethiopia, and so Operation Solomon was set in motion. Thirty-four El Al passenger planes were requisitioned, their seats were removed to maximise capacity, and over the course of thirty-six hours 14,325 Beta Israel Jews were covertly airlifted to safety in Israel.

Those who oppose Jewish statehood and sovereignty in our ancestral land — most of whom are non-Jews — often argue that Zionism cannot be a constituent part of ‘real’ Judaism, because it is ‘modern’, and represents a syncretisation of millennia-old Jewish beliefs with 20th century European concepts regarding politics and nationhood. The three Cherokee tribes today are also ‘modern’; their governments have been heavily influenced by the US model, with written constitutions and executive, legislative and judicial branches. This does not give non-Cherokees licence to question the legitimacy of these tribes as representative of 21st century Cherokees.

The Arab League, the de facto inheritor of much of the Islamic empire — at its height the seventh largest empire in recorded history — comprises twenty-two sovereign states, spans 5.1m square miles, and has a combined population numbering well over 420m. The League has consistently targeted Israel for military aggression, and diplomatic condemnation and isolation, while simultaneously denying the indigenous rights of non-Arabs within their own countries. The true injustice in the Middle East and North Africa is not the existence of a single Jewish state, carved out of a sliver of the Levant equivalent to 0.17% of the lands controlled by the Arab League, but the fact that no similar states exist to represent the sovereignty of Copts, Imazighen, Kurds, Assyrians, and many other truly distinct and persecuted peoples.

Those who have read my other essays, or my ‘About the Author’ spiel, will know that I strongly oppose abuses by the State of Israel against Palestinians, and fully support Palestinian self-determination and statehood, but not at the expense of Jewish self-determination and statehood. I have written this essay because until Jewish peoplehood is respected, and our right to statehood within the bounds of our ancestral homeland is universally acknowledged as legitimate and just, I cannot see a path to peace for Jews and Palestinians.

While writing the conclusion to this essay I saw in Haaretz (a left-leaning Israeli newspaper) that the Washington, D.C. chapter of the Sunrise Movement, a climate change activist group, had announced that it would not participate in an upcoming voting rights rally because three progressive Jewish-American groups, which it labelled ‘Zionist organisations’, will be in attendance. A representative of Sunrise Movement D.C. stated: ‘given our commitment to racial justice, self-governance and indigenous sovereignty, we oppose Zionism and any state that enforces its ideology’.

Zionism is literally a commitment to self-governance, indigenous sovereignty, and justice. For the Jewish people.

1. An earlier version of this essay stated that Hebrew was 'largely replaced by Aramaic, a closely related Semitic language, as the vernacular in Eretz Yisrael as early as the 6th century BCE'. Having learnt more about the history of Hebrew as a spoken language, and its complex relationship with Aramaic, I have revised my position on this. For more information I highly recommend Joel M. Hoffman's wonderful book In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language.

2. Although not traditional, the communal 'hog fry' is a staple of modern Oklahoma Cherokee cuisine.

Adair, J. (1775) History of the American Indians

Conley, R.J. (2005) The Cherokee Nation: A History

Conley, R.J. (2007) A Cherokee Encyclopedia

Foreman, G. (1938) Sequoyah

Hoffman, J.M. (2004) In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language

Kilpatrick, J.F., ed. (1966) The Wahnehauhi Manuscript: Historical Sketches of the Cherokees

Mooney, J. (1891) The Sacred Formulas of the Cherokees

Mooney, J. (1902) Myths of the Cherokee

Mooney, J., ed. and Olbrechts, F.M., ed., (1932) The Swimmer Manuscript: Cherokee Sacred Formulas and Medicinal Prescriptions

Ostrer, H. (2012) Legacy: A Genetic History of the Jewish People

Page, J.A.C. (1996) Index to the Cherokee Freedmen Enrollment Cards of the Dawes Commission, 1901-1906

Perdue, T. (1998) Cherokee Women: Gender and Culture Change, 1700-1835

Perry, M.J. (1974) Food Use of Wild Plants by Cherokee Indians

Roden, C. (1996) The Book of Jewish Food

Scheindlin, R.P. (1999) The Gazelle: Medieval Hebrew Poems on God, Israel, and the Soul

Thornton, R. (1990) The Cherokees: A Population History

Thorowgood, T (1660) Jews in America, or Probabilities, that those Indians are Judaical, made more probable by some Additionals to the former Conjectures

Wardell, M.L. (1938) A Political History of the Cherokee Nation, 1838–1907